Abstract

While much of contemporary psychotherapy practice often focuses primarily on verbal exchange between therapists and clients, it is important to recognize that verbal expression is just one mode of expression, and not necessarily the deepest or most profound. Many clients in therapy may be more comfortable in expressing themselves in other ways through the modes of music, art, dance and psychodrama.

The sources of the arts in healing extend back for many thousands of years and their modern expression through the creative arts therapies are now widely utilized in the mainstream of modern psychotherapy. Traditional healing practices are still widely practiced in many indigenous cultures around the world today and an appreciation of these practices can deeply enrich our understanding of the essential role of the arts in human expression.

The aim of this paper is to consider the roots of the arts therapies and really all of psychotherapy, going as far back as pre-historic evidence, followed by an overview of living indigenous healing practices in such settings as Bushman culture in Namibia, Native American Indian culture, as well as in Kenya, Bali, Malaysia, Mongolia and more.

---------------

In considering the historical development leading to the current applications of music therapy as a professional discipline it is crucial to remember that music therapy is not a recently developed modality. Rather, music therapy as a profession is only a recent and specialized line of development of the continuing 35 thousand-year-old shamanic traditions of music and healing still being practiced throughout the world. By comparison, music therapy in the United States has had little more than a 50-year history of professional recognition.

Music as therapy, without being described as “music therapy”, is currently a flourishing practice in countless tribal and other non-technological societies in Asia, Africa, Australia, America, Oceania and Europe. That so much of the music of these cultures is oriented toward healing traditions becomes particularly apparent in the ethnomusicological literature. A survey of world music traditions (May, 1983) covers 19 representative culture areas, with individual chapters written by some of the world’s foremost ethnomusicologists. It is remarkable, for example, that the chapters about the musics of Indonesia, the Australian Aboriginals, several sub-Saharan African cultures, the North American Indian, Alaskan Eskimos, South American Indian music, and aspects of other cultures are overwhelmingly oriented toward the role of music and healing in the shamanic tradition. The chapter by Olsen, “Symbol and Function in South American Indian Music” (1983), is devoted almost entirely to the role of music in shamanic practice. Singing and drumming are discussed in relation to their roles as the principal stimuli utilized to induce states of shamanic ecstasy. Indeed, this chapter is a substantial treatise in itself on music and healing practices in tribal cultures.

In the chapter examining the black music of South Africa, John Blacking (1983) refers to the highly social nature of subSaharan music in general, where individual parts may interlock in rhythmic polyphony (the hocket technique) to create the whole. His description of this kind of performance is an ethnomusicological

expression of the concept of rhythmic entertainment that has become the focus of a growing body of music therapy research: “Anyone who has performed in such ensembles will know just how the music generates a change of somatic state when all the players or singers of different parts slot into a common movement.”

The “common movement” that Blacking refers to is analogous to the “phase locking” that occurs in rhythmic entertainment, when two or more objects that are pulsing at nearly the same time tend to “lock in” and begin pulsing at the same rate. In this can be seen a common element between the rhythmic connection that can exist between the shaman and patient and between the music therapist and client. In both instances, rhythm can bring the two together on a level that is distinct from verbal communication and that is perhaps even more basic and significant. It seems unlikely that these world traditions of music and healing could have survived for 35 thousand years, or more, unless they had been found to be empirically effective (Harner, 1982). This legacy poses a special challenge for the music therapist to interpret its significance for contemporary music therapy theory and practice.

A serious re-examination of these living world traditions of music and healing in shamanic practice can help to: a) enhance our understanding of the relationship of music therapy to other psychotherapeutic modalities, (b) clarify the role of music therapy in response to current trends in holistic healing and the integration of the creative arts therapies, and c) clarify points of understanding about the most basic meaning of music as therapeutic modality.

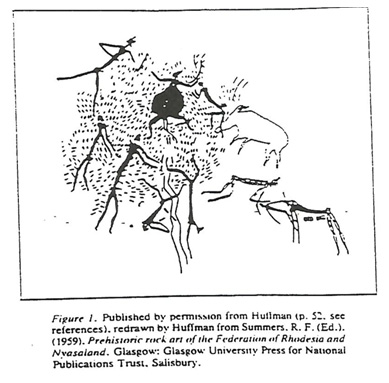

An examination of prehistoric documentation can be highly revealing. The illustration in Figure 1 is of a Bushman rock painting from Zimbabwe in Southern Africa that is estimated to be about 26 thousand years old (Huffman, 1983).

This painting seems to represent some of the earlist visual documentation of music and healing and to illustrate the musical element within a holistic paradigm. Huffman (1983) describes the central figure as a mother goddess surrounded by dancing figures presumed to be in a trance state. The male figure in the upper right is clapping to accompany the dancers and providing the rhythmic musical support that sustains the trance. Lewis-Williams (1981) has drawn on Bushman ethnography to support explanations of Bushman rock art that emphasize trance performance. The Bushman medicine men still enter trance during medicine dances, and these beliefs are shared by Bushman groups throughout Southern Africa. Furthermore, Lewis-Williams’ trance metaphor has demonstrated relevance to rock art, compatibility with anthropological theory, predictive potential, and simplicity. Other interpretations, in contrast, have little explanatory power because they are merely ad hoc inductions (Huffman, 1983). It has also been demonstrated that prolonged violent rhythmic dancing may cause hyperventilation (Jones, 1954) that also contributes to trance.

This superficially simple 26 thousand-year-old painting can have a stunning impact if one considers its full implications. Within the painting there seems to be a perfectly explicit depiction of the holistic integration of the creative arts therapies in healing (i.e., music, art, dance and drama).

The music is illustrated by the clapping accompaniment, and the dance appears to be clearly depicted. Art is represented by the very creation of the painting, and the implied healing ritual would represent a dramatic experience enacted between the group of participants and the spirit world.

According to Huffman (1983) the symbolic components of the painting, such as the wavy lines, represent bees, which were special power animals to the Bushman, and the special powers attributed to the figure interpreted as a menstruating goddess further suggest the enactment of tribal myths in healing ritual.

Prehistoric paintings such as this one strongly suggest a connection between music, art, dance and drama in the healing process. This integration of the creative arts therapies, this interdisciplinary cooperation, which the respective American organizations for music, art, dance and drama therapies are just beginning to initiate, was probably well-established at least 35 thousand years ago. The painting also suggests that the group therapy process, another relatively new trend in psychotherapy, has always been as integral to tribal healing rituals as it is today.

The holistic integration of music, art, dance and drama in healing rituals in both historic and contemporary practice in cultures throughout the world provides a strong empirical model from which to formulate an approach to music therapy relevant to the mainstream of Western culture.

The shaman, whether referred to as a “medicine man’, “witch doctor” or by any other term, is the prototypical healing figure and music therapist, and has always been a multidisciplinary practitioner – a holistic healer. A shaman never specializes in only music, or art, dance, or drama. Instead, he or she naturally integrates all of these elements into practice. For example, in American Indian culture the Navajo medicine man or woman would never only sing a medicine song to function as a specialized kind of “music medicine man”, and then call upon other healers to carry out the ritual dances, do the sand paintings, the dramatization of the tribal myths, the verbal interactions with the patient, and so on.

And yet, as absurd as this might seem,this separation represents precisely the kind of therapeutic compartmentalization and overspecialization that occurs in our own culture. Professional training programs tend to create single focus therapists who lack the necessary breadth of background to holistically draw from sources in the other creative arts. Although there exist a few progressive institutions in which teams of creative arts therapists work together cooperatively, it is certainly the exceptional institution in which all of the creative arts therapists are fully represented in treatment programs. Greater versatility on the part of individual therapists might be a more feasible goal than that of having teams of four creative arts therapists, each with a different specialty, in every institution.

By contrast, the medicine man or woman not only integrates sources from all of the creative arts, he or she never holds a compartmentalized view of a patient. Traditional healers view patients from a broad social perspective, and never attempt any cure without full consideration of their patients’ emotional, spiritual, and physical state. They would never consider the musical part of the treatment as an element separate from the whole – or in any way separated from the total needs of their patients. Their “goals”, if they would express themselves in those terms, would not focus on a single aspect of their patients – like some goals characteristic of the behavioural approach to music therapy, that is, “the patient will make more positive statements” or “the patient will spend less time in isolation”. Rather, the medicine man or woman looks at the patient as a total human being and thinks in terms of the patient’s total life adjustment.

This holistic model certainly has many immediate implications for the education and practice of the music therapist, as well as for all therapists working in the creative arts. In this writer’s view, it is unfortunate that music therapists in their professional training in the United States do not receive instruction in art and art therapy, and that dance therapists do not receive instruction in drama and drama therapy, and so on. The model of the traditional healer suggests that the professional training of the music therapist ought to include at least introductory level courses in art, dance, and drama and their therapeutic applications. In this way, music therapists, although still retaining a primary musical identity, could enrich their work by holistically integrating sources from the other creative arts.

In practice many music therapists often do involve their clients in therapy experiences that integrate music with the other arts, such as music and movement or music and art expression. However, they typically lack the training to pursue these directions with any real depth or confidence. These practices seem to reflect their feeling that a one-dimensional music-only approach is too limiting, both for themselves as therapists and for their patients. At the same time, many music therapists who do integrate the other creative arts into their practices may do so with misgiving, as if they have somehow betrayed the purity of their discipline. The shaman’s holistic model should dispel all of these doubts.

A further implication from the shamanic model is suggested for the music education of the music therapist. Shamans typically have to deal only with patients from their own culture group. Musical materials, as assimilated through the culture, need only reflect the music of a homogenous cultural group. However, the music therapist who lives in a multi-cultural society needs to develop some degree of ability in a wide variety of ethnic musical genres in order to enhance the possibilities of establishing musical communication with patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds. The use of these ethnic musical associations might not always be indicated in practice, but the music therapist should certainly have the necessary breadth of musical background to utilize these possibilities when they are called for. This suggests that a holistic music education for the music therapist should include required coursework in world music or ethnomusicology.

The shaman is a specialized figure in tribal cultures. The shaman is more than a medicine man or woman administering herbal medicines and functioning in a medical way. The shaman has more visionary abilities. A shaman is defined by anthropologist Michael Harner (1982) as “… a man or woman who enters an altered state of consciousness – at will – to contact and utilize an ordinarily hidden reality in order to acquire knowledge and power to help other persons.”

Central to the shaman’s task of entering the state of altered consciousness that is crucial to the healing process is the use of rhythmically hypnotic and repetitive supportive music, most typically in the form of rhythmic drumming. Neher (1962) investigated the role of rhythmic drumming as a physiological stimulus in trance inducement by attempting to replicate the shamanic drumming stimulus in a controlled laboratory experimental situation. In this manner, the experimenter was able to closely monitor subject responses. Neher’s research indicated that the experimentally controlled drum beating induced symptoms of trance-like states similar to those observed in shamans in an altered state of consciousness. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to measure the physiological responses of shamans and patients in real healing situations, as the intrusive nature of attempting to introduce monitoring equipment into highly sacred and private ceremonies minimizes these possibilities. Neher’s data indicated that:

- A single beat of an untuned drum contains many frequencies, so that the different overtones are transmitted over different pathways in the brain. He concluded that the resonant sound of a drum can stimulate larger areas of the brain than a less complex single frequency sound.

- A drum beat contains many low frequencies, and the frequency receptors for low frequencies are so much stronger than the delicate high frequency receptors that the listener can tolerate low frequency pitches for a longer time before pain is felt. As a result, more energy can be transmitted to the brain with a drum than with a higher frequency stimulus.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) measurements of Neher’s subjects indicated that the typical tempo of tribal drumming, replicated in the experimental setting, was close to the basic rhythm of alpha wave production (8-13 cycles per second). Additionally, the drumming produced an auditory driving of the alpha waves leading to a trance-like state in the subjects.

Finally, the subjects reported that they had experienced unusual perceptions in the trance-like state similar to those described by traditional healers, indicating an altered state of consciousness. Neher’s research seemed to have experimentally provided measurable physiological data that supported what has long been empirically experienced and understood by traditional healers. However, it is possible that Neher’s data were crucially flawed in that he was unable to control for movement artifact in his EEG measurements (Achterberg, 1985).

Rouget (1985) believes that music should ultimately be seen as more than only a rhythmic stimulus in trance inducement. Rouget suggests that though music is the principal means of manipulating the trance state, it does this by “socializing” it more than by simply triggering it. This process of socialization varies from culture to culture, according to the ideological system within which trance takes place. While Rouget emphatically rejects Neher’s conclusions, short of definitive data on this highly complex issue, the relationship between the psychological and physiological role of music in trance inducement remains an open question.

In order for shamans to be effective healers, they need to enter a state of “non-ordinary reality”, an altered state of consciousness. This altered state is necessary to free the shamans so that they can “travel” (in shamanic terms) to the spirit world, either in order to remove harmful spirits from the patients or to restore beneficial ones. Shamans are well aware that these spirits do not exist in “ordinary reality”, and in any case, a “spirit” is perhaps no more of an abstraction than such theoretical concepts as “id”, “ego”, “super-ego” and other analytic constructs (Harner, 1982).

In order to reach the spirit world, shamans must be internally focused and able to fully concentrate on the task at hand. Therefore, the music (drumming, or other rhythmic musical stimuli such as chanting or the playing of rattles, etc.) is often made or supported by an assistant or group of assistants so that the shamans will not have to be distracted by the actual music-making. The music affects the shamans psychologically and physiologically by supporting an alpha state in the manner previously cited (Neher, 1962), and also blocks out any distracting stimuli. For the experienced shaman, the musical stimulus alone can immediately trigger the response whereby he or she enters an altered state of consciousness. This is a response that has been conditioned by association with all previous similar experiences.

The hypnotically repetitive rhythmic music can be seen as a sedation of the left hemisphere of the shaman’s brain, the hemisphere that might otherwise be concerned with distractions of “ordinary reality”. This sedation then liberates the right hemisphere of the brain to travel to the spirit world, a journey that is integral to the healing process. In more poetic shamanic terms, the drum is seen as the shaman’s horse that allows him or her to fly to the sky to encounter the world of the spirits (Eliade, 1974).

The musical stimuli have values for the patient as well. Rhythmic music also allows the patient to enter a receptive semi-hypnotic state that reinforces belief in the power of the shaman and of the healing ritual. Shamans may also make use of special medicine songs that symbolize the power of the ritual and further enhance patients’ faith in the ability of shamans to heal and in their commitment to their patients in calling upon the sacred songs. As Frank (1972) has stated, “The success of all methods and schools of psychotherapy depends in the first instance on the patient’s conviction that the therapist cares about him and is competent to help him”.

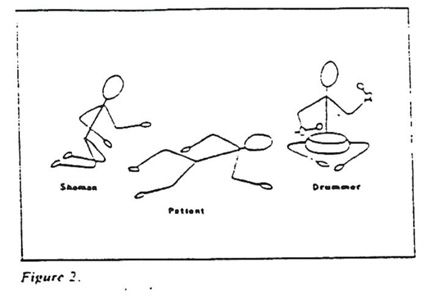

Figure 2 illustrates the physical arrangement of the most basic shamanic music and healing situation. In this model, the oldest psychotherapeutic context known to mankind, it can be seen that music is intrinsic to the psychotherapeutic process. Without the musical support, shamans in most cultures would find it difficult to travel to the spirit worlds.

The model also provides a basis for suggesting that music contributes an essential element to therapy that should never have been eliminated from modern Western therapies. For example, in Western-oriented culture, a verbal therapist such as an analyst has many therapeutic goals in common with the shaman. Like the shaman, analysts need to minimize distracting left brain stimuli in order to focus on a right brain intuitive connection with the patient. The analyst also tries to process the patient’s experiences by evaluating them in relation to his or her own life experiences and knowledge, just as the shaman “brings into play his or her past experience of affliction and transcendent realization in relation to one who is now suffering” (Halifax, 1979). This process requires a great deal of introspection, concentration, and a high level of sensitivity to the patient’s feelings and needs. The shaman seeks to contact the appropriate guardian spirits and connect these to the needs of the patient.

Despite their differences in approach, both the shaman and the analyst need to be able to focus entirely on the process of the moment, sensitize themselves to the needs and feelings of their patients, and to remove themselves from their ordinary state of being. However, the shaman takes advantage of the facilitating support system of music, of which the analyst and patient are entirely deprived. The analyst is still able to complete his or her task, but the process is that much more difficult for both therapist and patient.

Music therapists, in common with shamans, take the fullest possible advantage of music in the therapeutic process. In music therapy, the musical element becomes the primary focus. The musical element in music therapy in Western culture takes on an even broader role than the music in traditional healing. Without the universally shared world view and unquestioning faith in the healing ritual that is such a supportive element in those tribal cultures in which shamanic healing occurs, the music becomes the binding force. The musical experience alone can create a bond between therapist and client, help to summon the client’s regenerative forces and a belief in the therapist’s healing ability, and ultimately realize a contemporary Western expression of the traditional music and healing rituals.

Finally, the traditional interactive model of shaman, drummer and patient (see Figure 2) suggests that music therapists should not lack the confidence to fully interact with their patients verbally and to pursue in-depth verbal processing of their patients’ experiences and feelings. There should be no separation in theory of practice between the musical and verbal elements in music therapy – neither should be used separately. Called for is a holistic integration.

It is of interest to further examine the shaman’s characteristic use of musical assistants. By making frequent use of an assistant to help in the physical act of music making, shamans free themselves to travel without distraction to the spirit world. Music therapists often follow this model intuitively, by utilizing, when possible, a co-therapist to make music so that they can interact more directly with the patients. Also, technology has provided an always available musical assistant through the medium of recorded music, which can meet the music therapists’ same needs of physical and mental liberation. However, sometimes shamans may create their own musical support, just as music therapists can also function entirely independently.

Observing music and healing rituals in various world cultures provides contemporary evidence of the continuity of these traditions. Balinese culture in Indonesia provides many interesting examples. Trance is a common form of ritual practice in Bali and serves many functions. Trance provides a kind of emotional outlet for people living in a highly ritualized and predictable culture, often serving as a kind of exorcistic function, and always in the context of a musical setting. Associations with the special gamelan music played during the trance dance is trance-inducing, just as the drumming becomes trance-inducing for the shaman. Usually, young girls are chosen to be trance dancers, called upon, for example, in rituals designed to ward off epidemics. These prepubescent girls represent a kind of purity to the Balinese that allows them to be entered by the gods, as evidenced by their trance-like state. The dancers, in turn, incite many of the participant observers to go into trance as well.

The recent use of the Paiste Sound Creation Gongs in Europe as a specialized instrument and approach in music therapy is directly derived from Indonesian traditions. The Sound Creation Gongs are a set of eleven untuned gongs, designed for work in music therapy. Each going has a unique and contrasting timbre. The sound polarities lend themselves to the expression of emotional polarities (i.e. calm vs. anger) and gong sounds have the additional value of being unconditioned sound stimuli, with the potential of being able to elicit relatively spontaneous musical responses not limited by previous musical associations.

In Indonesia, the large gong in the Javanese gamelan is the most honoured and the most sacred instrument. Special offerings to the going are made weekly to appease the spirits that live within and around it (Lindsay, 1979). In general, Javanese gamelan performers associate performance of the music with a state of peace and detachment, again reminiscent of the shamanic alpha state. These connections between gamelan music, trance, exorcism, the Indonesian and Western uses of the gong, and even in the Western re-creation of gamelan style instruments in the Orff Schulwerk (also broadly utilized in music therapy) are all representative of the continuing links between modern music therapy and traditional music and healing. The Orff xylophones, created for use in music education and therapy, were modelled directly after the Indonesian gamelan instruments. Like the gamelan xylophones, they have the possibilities for providing the immediately gratifying music making that can be so useful in therapy.

In a variety of contemporary African cultures it is still possible to observe healing rituals that in their integration of all the creative arts in the healing process provide a striking parallel to the image previously discussed and portrayed in Figure 1. In Southern Africa, the Shona people of Zimbabwe have healing rituals called bira ceremonies (Berliner, 1981). The rhythmic music played by the mbira is intrinsic to the ceremony.

In Shona religion, a basic tenet is that after people die their spirits continue to affect the lives of the living. The living must try to continue to maintain good relations with the spirits of the departed. If they do not manage these relationships effectively, the Shona consider it inevitable that they will have serious problems of some kind. When the problems cannot be dealt with in any other way, the Shona organize a bira ceremony. The whole family or community gathers to summon the ancestor’s spirit for help, and the shaman serves as a spirit medium.

In the context of the highly rhythmic mbira music, which is played all night, along with continual dancing and the drinking of specially prepared ritual beer, the shaman becomes possessed by the spirit, then “becomes” the spirit, and only then can he or she help the patient (Berliner, 1981). As is suggested in Figure 1, the Bushman rock painting, the rhythmic music and dancing support the spirit-mediums in their trance-like state. In Balinese culture, as previously stated, the music supports the dancers in entering the altered state of consciousness that is intrinsic to the therapeutic process.

Traditional Music and Healing and Contemporary Music Therapy Techniques

Many interesting parallels can be drawn between the role of music in traditional healing, rituals and a contemporary re-expression of some aspects of these practices in music therapy techniques. For example, a technique such as guided imagery and music has a very obvious relationship with shamanic practice (Kovach, 1985)

In guided imagery and music, the patients rather than the therapist (the symbolic shaman) enter an altered state of consciousness. This is acquired through deep relaxation and concentration on the music, which can induce a trance state similar to that which occurs in shamanism. In guided imagery, the patients travel to their own inner world of conflicts and other personal issues rather than to spirit worlds. In both instances an inner vision is essential.

As in shamanism, the darkened room and the music help the patient to focus on unconscious feelings rather than on the superficial realities of ordinary daily life. During the imagery session, patients are in a different reality, focusing on repressed conflicts or other difficult material that in many ways can be more real than their ordinary reality.

The music therapist, like the shaman, is still necessary to help patients verbally process their experiences and gain insight into their feelings. Another interesting parallel is that the changes in mental imagery in response to the varying character of the supportive music in guided imagery are similar to the changing shamanic visions in response to changes in the tempo or timbre of the drumming.

Achterberg (1985) has stressed the continuum between the shaman’s use of imagination in healing and the growing use of imagery in general medical practice. Imagery is a pervasive element in shamanic healing that is fully adaptable to the cultural context of modern medicine and to applications of music therapy with a specific medical focus. For example, in the work of Rider (1987), improvised music, rhythmic entertainment and imagery are combined for the purposes of pain management and for measurable disease control. This is exemplified by the case of a diabetic patient who demonstrated a marked decline in blood sugar variation in response to this personalized approach to music and imagery. As Achterberg (1985) has stated, “the finest medicine will be produced by those who take the best from the shaman and the scientist”.

Still another parallel can be seen in the integration of art and music in music therapy, that is, the patient freely draws in a self-expressive way in response to selected music stimuli analogous to the use of sand painting and music in the healing rituals in the Navajo culture of the American Indian. Although the approaches are entirely different, there does exist the common element of art and music expression integrated into the healing process.

In the same manner, the integration of music with dance of movement expression in music therapy has a direct relationship to the kind of ritual depicted in the Bushman rock painting in Figure 1. Music and hypnotherapy and music and psychodrama (Moreno, 1980, 1984) are two other integrated approaches with obvious relationships to traditional practices that are becoming more accepted in response to a growing holistic consciousness in the field of music therapy.

Directions for Future Research

Music therapists should become involved in collaborative field research with ethnomusicologists to study music and healing rituals from a multidisciplinary perspective. Ethnomusicologists have studied tribal music and healing ritual (Bahr & Haefer, 1978), but often the focus of the research has been on the musical and ritual elements of the healing, without real attention to either the immediate or long-term effects of the healing upon the patient.

Collaborative research between music therapists and ethnomuicologists could combine serious study of the music and ritual along with the maintenance of data on the patients’ responses to treatment. This kind of research would also help to determine the possibilities of adapting some of these traditions of music and healing techniques to the mainstream of Western music therapy. There is a sense of urgency regarding this research because many of these traditional healing practices are rapidly disappearing in response to urbanization and other acculturative influences.

Toward an Independent Theory of Music Therapy

Music therapy as a therapeutic modality has tended to explain itself in terms of the frame of reference of other psychological theories, such as behavioural therapy, psychoanalytic theory, and others. In this manner, the music therapist working in a behavioural context conceptualizes music as a positive reinforce to realize a contingent goal, or in psychoanalytic terms conceptualizes music as an experience that can be ego supportive and expressive of the libido without superego censure. These explanations of music therapy theory, through the framework of other psychological theories, point to the fact that an independent theory of music therapy that would explain itself largely in its own terms is still lacking. An exhaustive study of the common elements in music and healing rituals throughout the world could provide the data needed to develop this kind of theoretical basis for a more independent theory of music therapy that would express itself primarily from a music frame of reference.

This could represent a major breakthrough in an understanding of the music therapy process. Building the entire theoretical constructs of music therapy on a foundation of controlled research, based only in a Western culture setting, eliminates from consideration all of the continuing world traditions of music and healing, of which music therapy as a profession is only one extension.

The deepest aspects of these rituals cannot be experimentally replicated because they are such an intrinsic part of the various culture systems in which they are practiced. Despite this, they can and should be studied, both in the field and through the extensive anthropological and ethnomusicological literature. Again, despite the vast cultural differences between tribal societies and modern Western cultures, there are many commonalities in the use of music in healing in both settings.

Music therapy related research has amply demonstrated and measured the effects of music on human behaviour, both psychologically and physiologically. Music itself has been explained from the point of view of the physics of sound and from artistic, musicological, and ethnomusicological frames of reference. Nevertheless, despite the vastness of all this knowledge, the modern music therapist in practice is not so far removed in many essential ways from the traditional healer. The conceptions and the terminology have changed, but music still serves much the same purpose that it always has. The connections between tribal practices and contemporary music therapy are too strong to be ignored or merely dismissed as an historical legacy. They are vital and living connections that should be strengthened rather than severed.

In considering the historically persistent role of music in healing throughout the world from a Jungian point of view, it would appear that music has a strong archetypal significance for the human species. Shamans have always been intuitively aware of the archetypal power of music in healing, and this is evident in the spiritual and dramatic power of their practice. Music therapists in Western culture may diminish this connection with the archetypal power of their therapeutic medium of music when they fail to maximize the emotional depth of their work. The borderline between recreational music and in-depth music therapy could be partially measured by the extent to which the music therapist creates musical experiences of deep emotional meaning for clients and engages them in serious experiences. The music therapist needs to approach the power of the shaman, who takes the spiritual depth of the work for granted.

Music therapists can learn a great deal from the shamanic model: to grow in imagination, in sensitivity, in awareness of the archetypal power of the musical experience, and in the creative and expressive freedom of their work.

Jung, who had a good musical background, eventually stopped listening to music. He felt irritated “because music is dealing with such deep archetypal material and those who play don’t realize this” (Tilly, 1956/1977, p. 274). The shaman, by contrast, has always been close to the archetypal significance of music, and this sensitivity can be incorporated into the work of the contemporary music therapist. Deeply impressed by a music therapy demonstration. Jung went on to say, “I feel that from now on music should be an essential part of every analysis. This reaches the deep archetypal material that we can only sometimes reach in our analytical work” (p. 275). The archetypal work of the traditional healer can provide an exciting and liberating model that can open new possibilities for a renewed dynamic and spiritual emphasis in music therapy.

References

Achterberg, J. (1985). Imagery in healing: Shamanism and modern medicine. Boston: Shamohaia Publications.

Bahr, D. & Hacier, R. (1978). Songs in piman curing. Ethnomusicology, XXII.

Berliner, F. (1981). The soul of mbira. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blacking, J. (1983). Trends in the black music of South Africa. In E. May (Ed.). Muses of many cultures: An introduction. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Eliade, M. (1974). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Bolligen Series 76. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Frank, J. D. (1974). Persuasion and Healing (rev. ed, p. 165). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Halifax, J. (1979). Shamanic Voices (p. 317). New York: Dutton.

Harner, M. (1982). The Way of the Shaman (p. 25). New York: Bantam Books.

Huffman, T. N. (1983). The trance of hypothesis and the rock art of Zimbabwe. In J. D. Lewis-Williams (Ed.). New approaches to Southern African rock art. The South African Archaeological Society, Goodwin Series, IV.

Jones, A. M. (1954). African rhythm. Africa 24, 26-7. Studies in African music (2 Vols.). London: Oxford University Press.

Kenny, C. (1982). The Mythic Artery. Atascadero: Ridgeview Publishing.

Kovach, A.M., Stein- (1985). Shamanism and guided imagery and music: A comparison. Journal of Music Therapy. XXII (3).

Lewis-Williams, J. D. (1981 a). Believing and Seeing: Symbolic Meanings in Southern San Rock Paintings. London: Academic Press.

Lindsay, J. (1979). Javanese Gamelan. London: Oxford University Press.

May, E. (Ed.) (1983). Musics of Many Cultures: An Introduction. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Moreno, J. (1980). Musical psychodrama: A new direction in music therapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 17(1).

Moreno, J. (1984). Musical psychodrama in Paris. Music Therapy Perspectives 1. (IV)

Neher, A. (1962). A physiological explanation of unusual behaviour in ceremonies involving drums. Human biology 34(2).

Olsen, D. (1983). Symbol and Function in South American Indian Music. In E. May (Ed.) Musics of Many Cultures: An Introduction. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Rider, M. S. (1987). Treating chronic disease and pain with music-mediated imagery. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 14(2), 113-120.

Rouget, E. (1985). Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations Between Music and Possession. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tilly, M. (1956, 1977). The therapy of music. In W. McGuire & R. F. C. Hull (Eds.). C. G. Jung speaking (pp. 274, 275). Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press. (Original 1956, in Memoriam, Carl Gustav Jung. Privately issued by The Analytical Psychology Club of San Francisco, 1961).

|