|

|

Heart to Heart: The Associative Pathway to Therapeutic Growth

Anthony Korner

Director, Department of Psychiatry, Westmead Psychotherapy Program

Senior Lecturer, University of Sydney

Email: anthony.korner@health.nsw.gov.au

Abstract

Language is constitutive of who we are as

people. Play between infant and carer has a strong influence on how language is

acquired and the way it becomes generative of self. It is the communicative

exchanges of life that create one’s sense of self and significance. When

individuals enter into “free play” in therapy, they embark upon an associative

pathway where distinct associations, emerging from what has been considered the

“id”, form the basis of an emergent self, probably mediated by

right-hemispherically determined communication. A case vignette illustrates a

transition involving a moment of emotional connection, followed by a

realization, at a later point in therapy, with discussion of both patient and

therapist perceptions of these moments and an illustration of underlying

physiology.

The importance of right-hemispheric regulation in the psychotherapeutic setting calls for a revision of Freudian notions of primary and secondary process. The affective basis of associational life needs to be seen in a normative, integrative way rather than as an unruly process to be overcome by a rational ego.

Keywords: Feeling, Self, Id, Right hemisphere, Primary process

Introduction

The relationship of language and feeling to the development of self is critical to human growth in general and to psychotherapy in particular. Emergence of self involves coordination of language and feeling in the context of relationships providing conditions of emotional safety and intimacy. Such a coordination has been termed “the true voice of feeling” (Hobson, 1985, p.93) implying a capacity, not only to use language, but to engage in community.

The role of right hemisphere and “right hemispheric thinking” in communication is now better understood. Where the left hemisphere deals sequentially with events and representations, looking at problems analytically and taking things “apart”, the right hemisphere is involved in the processing of simultaneous perceptions that “appear all at once”. It is essential to solving previously un-encountered problems and “putting the synthetic picture of the multimedia world around us back together” (Goldberg, 2005, p.196; cited in Meares, 2012, p.288). “Neuroscientific studies …now clearly indicate that right (and not left) lateralized prefrontal systems are responsible for the highest level regulation of affect and stress in the brain. They also document that in adulthood the right hemisphere continues to be dominant for affiliation, while the left supports power motivation” (Schore, 2014, p. 389). A range of research leads to the conclusion that when it comes to managing moment-to-moment engagement with life it is the right hemisphere that should be considered ‘master’ and left the ‘emissary’ (McGilchrist, 2013). Functionally the left hemisphere is dominant in analytic logical atomistic thinking while the right hemisphere is dominant in associative synthetic thinking, crucial to social engagement.

In psychoanalytic theory, the question of whether understanding relates to agencies within the mind (e.g.id, ego, and superego), or to the whole person concept of self, is important. The role of gender has also been a concern in psychoanalytic theory, evident in the writings of Freud, Lacan, Klein, etc. However, if the primary emphasis is on self and relationship (non-gendered terms) gender may come to be seen as somewhat less critical to the development of mental life. This is not to deny the importance of gender. Of course, when one considers the embodied nature of self, gender is a critical aspect. What is considered primary to experience and self is personal feeling and the flow of consciousness, shaped by the environment and, importantly, by language, with the right hemisphere likely playing an important integrating role.

What might this look like in psychotherapeutic practice? To illustrate, I refer to a therapy where two sessions were recorded about 20 months apart. Apart from audio-recording and transcription, the sessions also involved physiological recording of breathing and heart rates.

Clinical

vignette

A young man, mid-twenties, came into

therapy for about 4 years. There were issues around anxiety and low mood and

difficulty in establishing a career path with a degree of autonomy. The first

session was in the third year of therapy. The second was towards the end of the

therapy. In the earlier meeting the primary motif of self is a subjugated, suffering

self, often referred to as object; or as the suffering grammatical object,

subject to domination, and definition, by others. This position was illustrated

by a number of statements, including, “maybe I do feel like a

piece of meat a lot of the time” and “I feel like I’m

being lynched”.

Twenty months later client’s self is consistently presented as an actor among other players, one who can maintain autonomy, and a sense of existence, in the face of challenge. He describes making purchases, finding work, negotiating with institutions and with family on an adult level while reporting an increase in self-esteem: “maybe I can make it all work”. The ‘old self’ is remembered, making a connection with a traumatic time for the family, “it was like weathering a storm, we all just battened down the hatches and went to battle stations.... survival mode which wasn’t about grouping as a family, it was about every man for themselves”, suggesting a prior sense of alienation. The later session shows greater use of transitive, action-based language conveying the sense of someone who has a sense of agency in relation to the environment. It also had ‘space’ in the form of reflective pauses.

At the narrative highpoint of each session there are some interesting features. In the earlier exchange, there is a marked and shared positive emotional connection between patient and therapist although the subject matter involves reference to negative self-image:

Pt:

“a really bad image of myself, really bad self-esteem”

Th: “you wonder whether you could be loved”

Pt:“I just look at the bad parts of

myself….that’s what they see, so why would they want that?”

The sense of positive

emotional experience, despite the negative subject matter, was confirmed by

independent ratings of the transcript by both patient and therapist as ‘feeling

moved’ at this point of the session. The ‘moment of meeting’ illustrated here

is a primarily felt and shared experience of presence to each other, most

likely reflecting right hemispheric communication.

In the later session the highpoint involves, by contrast, a “calm” fairly neutral affect reported by the patient associated with significant pauses and a self-reported experience of realization, while the therapist felt ‘moved’:

Pt: “I just that

of Danny boy again, you know the hills are calling”

Th: “Are calling?”

Pt: “To find your calling (pause) I kind of

never understood that term fully until now like when I found my calling”

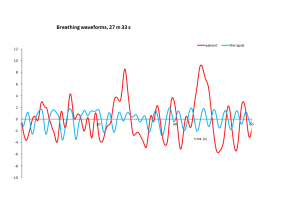

This exchange is, furthermore, associated with a distinct slowing of breathing, suggesting vagal down-regulation (Figure 1). Arguably there has been a transformation that had a starting point in the valuing of a previously negative image of self, allowing a shift in terms of agency and the capacity for reflection and integration of feeling and language. This second exchange illustrates the human process of realization representing personal growth. Arguably, the process of recognition and acceptance of vulnerability in the earlier session and the realization that occurs later are examples of the kind of social engagement underpinned by vagal regulation described in the polyvagal theory (Porges, 2011). It is likely there is active right hemispheric modulation of this “in the moment” experience of feeling states.

(insert

Figure 1)

*(a detailed exposition of this case can be found in Korner, 2015)

Discussion

In elaborating his ideas about primary and secondary process Freud recognizes a difficulty: “I have set myself a hard task, and one to which my powers of exposition are scarcely equal. Elements in this complicated whole which are in fact simultaneous can only be represented successively in my description of them, while, in putting forward each point, I must avoid appearing to anticipate the grounds on which it is based: difficulties such as these it is beyond my strength to master.” (Freud, 1900, p.745). Although he may not have been aware of it, he could be making the distinction between synchronic language and diachronic language; or between the whole and the parts. While Freudian elaborations are in terms of interacting parts, it can be seen that he had awareness of a whole, greater than the parts. He goes on to say that “primary process” is dominated by “activity..... directed towards securing the free discharge of the quantities of excitation” (ibid., p. 759), while secondary process, “succeeds in inhibiting this discharge”. Inhibition is crucial to the development of secondary process, and is also central to the Freudian theory of repression: “....it is key to the whole theory of repression: the second system can only cathect an idea if it is in a position to inhibit any development of unpleasure that may proceed from it” (ibid, p.761).

Thus, classical psychoanalytic theory sees secondary process (logical, goal-directed, rational thought; in touch with ‘external reality’) as an achievement, that results from inhibition of the unruly “primary process”. As such it is a form of rationalism, seeing development as the triumph of reason over passion. “Ideas” have an inherently linguistic form; whereas the term, “cathect”, means, “affectively invest”. It could be argued that the process of affective investment (“cathecting”) is primary in development, rather than ideas, given the pre-verbal infant has limited access to “ideas”.

Freud’s rationalist position is developed further, when he puts forward his “structural” theory of mind (Freud, 1923). The German version refers to “Das Ich” and “Das Es”, considered here in relation to the terms “I” and “it”, which seem closer to Freud’s intent. By using the latinized nouns “ego” and “id”, the translator, Strachey, may have contributed to reification of these terms relative to the original use of pronouns which denote as either personal or impersonal.

Freud states, “all perceptions… received from without... and from within – what we call sensations and feelings – are conscious from the start” (ibid, p. 18), thereby recognizing the centrality of feeling, to conscious states. This is not a notion that he develops, although he later says, “We approach the id with analogies” (Freud, 1933, p.4682), suggesting an understanding of the need to approach the representation of feeling through analogy.

While he recognizes the primacy of thinking in images, he sees it as a “very incomplete form of becoming conscious.... unquestionably older than (words)” (Freud, 1923, p.20). He refers to a passive experience in life where “we are ‘lived’ by unknown and uncontrollable forces”, seeing this as the perceptual system present from the start, and referring to this system as the “it”, consistent with “whatever in our nature is impersonal” (ibid, p.22 footnote). The impersonal “it” is seen as something “upon whose surface rests the ‘I’” (p.23), leading to the Freudian metaphor of the “I” being “like a man on horseback” (p.24), with “it” being the horse. The “I” has ever, “to hold in check the superior strength of the horse” (p.24). Specifically, he states that “The ego (“I”) represents what might be called reason, and endeavours to substitute the reality principle for the pleasure principle which reigns unrestrictedly in the id” (p.24). Reason is identified with language, known by Freud to be located in the left brain, reflecting the state of neurological knowledge at the time: “as we know, ... its speech (centre) ... (is) on the left-hand side” (ibid). In contrast, the “scene of the activities of the lower passions is in the unconscious” (ibid., p.25). The ‘location’ of the unconscious is “unknown”.

Freud asserts the significance of early relationships indicating a primary paternal influence in relation to this development: “in the origin of the ego ideal..... there lies hidden an individual’s first and most important identification, his identification with his father in his own personal prehistory” (ibid., p.30). He sees social feelings as arising out of the frustration of hostile impulses and feelings, “social feelings arise in the individual.... built upon impulses of jealous rivalry against brothers and sisters. Since the hostility cannot be satisfied, an identification with the former rival develops” (p.36). Social engagement is not seen as primary need or instinct but rather a compromise formation. He does not consider that hostility may arise out of traumatic circumstances. He contends, “Psycho-analysis is an instrument to enable ego (‘I’) to achieve a positive conquest of the id (‘it’) (ibid); expressed later as, “Where id was, there ego shall be.” (Freud, 1933, p.4687).

There are a range of positions on the role of language in healing and development of self (Berthold, 2009). Hegel saw language as essential to development of self, referring to the “divine nature” of language (Hegel, 1807). Difficult experience has potential to be modified by language: “The talking cure... puts the obscure, fermenting ‘something’ of insanity into words, and in this way gives a sort of clarity which, as Freud saw it, was the best that could be hoped for” (Berthold, 2009, p.300). Kierkegaard is more suspicious of words, suggesting that professors, full of fine talk should be “stripped”, to see what they are really made of: “Yes to strip them of their clothing, the changes of clothing, and the disguises of language, to frisk them by ordering them to be silent, saying: ‘Shut up, and let us see what your life expresses, for once let this (your life) be the speaker who says who you are” (Kierkegaard, 1967, cited in Berthold, 2009, p.300). Lacan, is often identified as neo-Freudian in his emphasis on the “word of the father”, or “‘the symbolic’, the domain of language, the key vantage point from which all other ‘registers’ of psychic life must be approached” (Lacan, 1966, cited in Berthold, 2009, 301). He sees therapy as essentially a task of evoking speech, “it might be said (therapy) ...amounts to overcoming the barrier of silence” or “to get her (the patient) to speak” (Lacan, 1964, in Berthold, p.301) suggesting the need to overcome inhibition for integration to occur. Kierkegaard, while suspicious of language, recognizes his dependence upon it, saying he gets ill when he doesn’t write. He has a version of “talking cure”, involving “indirect communication... designed to lead the reader to take responsibility for self-authorship – ... a cure whose talking will be elusive, strange, and mysterious...” (ibid., p.303).

Where Hegel, Freud and Lacan argue in different ways for the psychological ascendancy of rational language, Kierkegaard’s version of the place of language in healing could be taken to refer to recognition of the value of a form of expression, related to Freud’s notion of primary process i.e. the primary flow of conscious experience reflected in non-linear, associational thought. His reference, to letting one’s life “be the speaker” is consistent with humans as “living symbols”, occupying embodied places in communicative space that go beyond verbal language. He also contrasts the view of Hegel, later also found in Freud, of faith in objective knowledge, arguing that “truth is subjectivity” (Kierkegaard, 1967). This relates to recognition that the personal reality of the patient taking precedence in the therapy.

The integration of experience with language is an embodied process, more entwined with feeling than implied in Freud (where language is seen to be involved in a conquest, or mastery, of emotional forces). The recognition of the value of silence is also crucial to the notion of a space where self can grow which includes silent reflective space where, perhaps, “I” differentiates, and self ‘becomes’.

Mothers and fathers have always figured prominently in psycho-analytic theorizing, with good reason, given they are primary players in developmental process for any individual. Klein’s description of the “depressive position” highlighted early stages of development where the bond between mother and infant is central (Klein, 1935) as it is in so many analytic theorists. In elaborating development of self beyond the experience of “doer and done to”, Benjamin focuses on the importance of mother-infant attunement and mutual engagement, accounting for what she calls the “moral third”: a relationship based upon recognition of vulnerability in the other motivating care. She contrasts her position with Lacan’s: “Unfortunately Lacan’s oedipal view equated the third with the father, contending that the father’s “no”, his prohibition or “castration”, constitutes the symbolic third” (Benjamin, 2004, p.12). Her description of the development of the “third” relates more to processes of resonance, affiliation and empathy. This is a version of personal development not relying upon prohibition and inhibition but rather involving resonance and playful interaction.

Perhaps, rather than emphasizing either maternal or paternal influence, there is an advantage in seeing that what is being described is personal process, taking place in relationship. The “passions” represented by the horse, in Freud’s metaphor for related parts of the mind, of “rider and horse” (ego/id; I/it), devalue feeling as being of a lower order than the reasoning faculty of the mind, the “ego / I”. The metaphor is about learning to tame, or at least exert influence, over the dangerous, beast-like passions, naturally inclined towards aggression, competition and hostility. Language, as the tool of reason, is seen by Freud to be embedded in the left cerebral hemisphere, suggesting that the processing of the logical left hemisphere needs to inhibit and control the emotional right hemisphere. In this view, dominated by drives and the theory of repression, it is little wonder that expression by the patient of disagreement or failure to respond may get classed as “resistance” explained as natural hostility to superior reason.

Others have come to see the situation differently. In working with patients that displayed negative therapeutic reactions, Brandchaft commented that, “I believe that observation is being obscured in psychoanalysis by continuing to regard primary factors as defensive or secondary, while secondary factors are installed as primary. The primary factors in these patients proved to be the particular self-disorder emerging from the transference in the forms of archaic, intensified, distorted longings, now out of phase, which originally should have formed the basis of sound psychological structure.....The factors that proved to be secondary in these cases were drives; conflicts...castrations; separation; and superego anxieties” (Brandchaft, 1983, p.348).

We currently recognize that early development is informed by patterns of feeling, with affect regulation achieved through dyadic care and play. Such activity is modulated through right hemispheric influence, involving inhibition by the right orbito-frontal cortex of right-sided limbic and mid-brain structures (Schore, 2012; Panksepp & Biven, 2012) associated with effective regulation of affective experience in relationships. The left hemisphere can also exert an influence on affect, but is less effective in doing so. When the left-brain attempts to exert control through “‘verbal’, ‘logical’, and ‘analytical’” functions, with deficient right hemispheric modulation, the left brain may tend to “overpower”, the right brain (Doidge, 2009, pp.280-82). This may give rise to a dissociated, traumatic form of consciousness, rather than to an integrated experience of self.

Social engagement and the need for relationship are primary motivators utilizing feeling as an internal value system. Language can be affectively invested through playful and imaginative engagement. Indeed, without affective investment and affective expression (right hemispheric contributions) language is empty, lacking in conviction.

The id or “it” takes on a different value, when seen to include the affective heart of experience. Far from being “impersonal”, it is felt to be highly personal, while at the same time being an aspect of experience shareable with others, where similarity (“fellow feeling”) is sensed. Hence it is a critical bridge to communicative understanding. The patient referred to earlier comments in one session on a group that has “accused” him and left him feeling “exposed” seeing himself as an “it”. The situation is ameliorated when a member of the group says, “it’s not a crime to have feelings”. The patient responds to this: “I appreciated that, that’s a nice statement because it’s validating, it’s okay to have your feelings, you don’t have to be lynched even if you do have your feelings”. However, the task of finding a voice, or expressing what is felt, is challenging. It has to be approached analogically, and is never completely mastered.

Patients are likely to experience a challenge in finding “The words to say it” (Cardinal, 1984). It takes courage to express what is heartfelt. Rather than representing something impersonal or “beast-like” that needs to be tamed, or mastered, the affective heart of a person is a central motivator to be understood as the basis of creativity for any individual. Imagery is also to be understood as central to personal process, and to thought, more generally. It is not simply an inferior, or primitive, aspect of thought.

When we speak of self we speak of the whole, reflected in pronominal language: a process which includes, but is greater than, “I” and “me”. It is a singularity defined through personal inscription of feeling, not generic inscription of conceptual language. Linguistic analysis of healthy people expressing their experience tends to show alternation between “I” perspectives, and “other” perspectives, reflected in use of pronouns (Pennebaker, 2011). This suggests that, in health, the capacity for conversation, initially reliant upon the “actual” other, can be carried on within the stream of one’s own thought. Where trauma has significantly constricted this capacity, there is a need for facilitation of an effective voice of self, through the psychotherapeutic conversation.

The communicative response of self is understood as a coordination, or integration, of language and feeling, not a subjugation of feeling. In traumatic circumstances, the flexibility of feeling response is lost reflected in constrictions and dissociations in consciousness limitingdevelopment of self, understood as an unfolding process with inherent value. It is trauma that leads to distortions in maturation. “A mature self, when it emerges, is a generator of bodily space and time, in the first place for the person’s own self and then, with further development, becoming a generator of the kind of space for others that engenders players in the human world” (Mclean & Korner, 2013, p.7). The personal nature of feeling and imagery; involvement in conversations (in words and images) with others, and within ourselves, constitutes what is significant in human lives. While based in personal experience, it can be seen as transcending the personal, part of a chain of continuity with past and future generations.

References

Benjamin, J., Beyond Doer and Done To: An Intersubjective View of Thirdness. (2004). The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 78:5-46.

Berthold, D., Talking Cures: A Lacanian Reading of Hegel and Kierkegaard on Language on Madness. (2009). Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 16:299-311.

Brandchaft, B. (1983), The

Negativism of the Negative Therapeutic Reaction and the Psychology of the Self.

In, TheFuture

of Psychoanalysis. Ed. Goldberg, A. (pp. 327-359)

New York, International Universities Press.

Doidge, N., (2007). The Brain that Changes Itself. New York, Viking Penguin.

Freud, S., (1900), The Interpretation of Dreams. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, Pelican Books, 1976.

Freud, S., The Ego and the Id. (1923), In, The standard

edition of the complete psychological works of SigmundFreud. Vol XIX, London, Hogarth, 1949, pp.1-66.

Freud, S., New Introductory Lectures on

Psychoanalysis. (1933), In, The standard edition of the

completepsychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. XXII, lecture 31, "The Dissection of the

Psychical Personality, London, Hogarth, 1964.

Goldberg, E., The wisdom paradox. New York, NY, Gotham Books, 2005.

Hegel GWF. (1807), Phenomenology of Spirit (trans.

Miller AV) Oxford,

Oxford University Press, 1977.

Hobson, R. (1985), Forms of Feeling. London, Tavistock.

Kierkegaard, S., (1967), (trans. Hong, H., & Hong, E.) Kierkegaard’s journals and papers, (6 vols), Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Korner, A.J., (2015) Analogical Fit: Dynamic Relatedness in the Psychotherapeutic Setting. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

Lacan, J., trans. Grigg, R. (1964), The seminars of Jacques Lacan, book XI: The four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis. New York, Norton.

Lacan, J., trans. Fink, B. (1966) Ecrits. New York, Norton.

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The Master and his Emissary: the divided brain and the making of the Western world. New Haven and London, Yale University Press.

Mclean, L.&Korner, A., (2013), Dreaming the (lost) self in psychotherapy: beings in bodyspacetime in collision, confusion and connection. In (e-book), Inter-Disciplinary.net, Freeland, Oxfordshire, 2013; http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/

Meares, R. (2012), A Dissociation Model of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, W.W. Norton.

Panksepp, J. & Biven, L., The Archaelogy of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotions. (2012), New York, W.W. Norton.

Pennebaker, J.W. (2011), The Secret Life of Pronouns. New York, Bloomsbury Press.

Porges, S. (2011), The Polyvagal Theory. New York, W.W. Norton.

Schore, A.N. (2012), The Science of The Art of Psychotherapy. New York, W.W. Norton.

Schore, A.N. (2014), The Right Brain Is Dominant in Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 51:388-397.

Fig. 1 Breathing forms at the narrative climax of session, showing slowing of respiratory rate in the patient (10-11 bpm), possibly reflecting ‘vagal up-regulation’.